Monday, April 17, 2006

Neil Young- speaks and sings his mind

Protest music is back with Neil Young's 2006 release, 'Living With War', featuring many great songs/ideas including this one, "Let's Impeach The President".

Saturday, April 15, 2006

What Rumsfeld knew

Apr. 14, 2006 | Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld was personally involved in the late 2002 interrogation of a high-value al-Qaida detainee known in intelligence circles as "the 20th hijacker." He also communicated weekly with the man in charge of the interrogation, Maj. Gen. Geoffrey Miller, the controversial commander of the Guantánamo Bay detention center.

During the same period, detainee Mohammed al-Kahtani suffered from what Army investigators have called "degrading and abusive" treatment by soldiers who were following the interrogation plan Rumsfeld had approved. Kahtani was forced to stand naked in front of a female interrogator, was accused of being a homosexual, and was forced to wear women's underwear and to perform "dog tricks" on a leash. He received 18-to-20-hour interrogations during 48 of 54 days.

Little more than two years later, during an investigation into the mistreatment of prisoners at Guantánamo, Rumsfeld expressed puzzlement at the notion that his policies had caused the abuse. "He was going, 'My God, you know, did I authorize putting a bra and underwear on this guy's head?'" recalled Lt. Gen. Randall M. Schmidt, an investigator who interviewed Rumsfeld twice in early 2005.

These disclosures are contained in a Dec. 20, 2005, Army inspector general's report on Miller's conduct, which was obtained this week by Salon through the Freedom of Information Act. The 391-page document -- which has long passages blacked out by the government -- concludes that Miller should not be punished for his oversight role in detainee operations, a fact that was reported last month by Time magazine. But the never-before-released full report also includes the transcripts of interviews with high-ranking military officials that shed new light on the role that Rumsfeld and Miller played in the harsh treatment of Kahtani, who had met with Osama bin Laden on several occasions and received terrorist training in al-Qaida camps.

In a sworn statement to the inspector general, Schmidt described Rumsfeld as "personally involved" in the interrogation and said that the defense secretary was "talking weekly" with Miller. Schmidt said he concluded that Rumsfeld did not specifically prescribe the more "creative" interrogation methods used on Kahtani. But he added that the open-ended policies Rumsfeld approved, and that the apparent lack of supervision of day-to-day interrogations permitted the abusive conduct to take place. "Where is the throttle on this stuff?" asked Schmidt, an Air Force fighter pilot, who said in his interview under oath with the inspector general that he had concerns about the length and repetition of the harsh interrogation methods. "There were no limits."

Schmidt also saw close parallels between the interrogations at Guantánamo, and the photographic evidence of abuse at Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq. "Just for the lack of a camera, it would sure look like Abu Ghraib," Schmidt told the inspector general, in the interview that was conducted in August 2005. At the direction of Pentagon officials, Miller led a mission to Iraq in August 2003 to review detainee operations at Abu Ghraib -- a visit that critics say precipitated the abuse of prisoners there.

In April 2005, Schmidt completed his report on detainee abuse at Guantánamo, which he co-authored with Brig. Gen. John T. Furlow. They recommended that Miller be "admonished" and "held accountable" for the alleged abuse of Kahtani. But that recommendation was rejected by Gen. Bantz J. Craddock, the current head of the Southern Command, who said Miller had not violated any law or policy.

On Dec. 2, 2002, Rumsfeld approved 16 harsher interrogation strategies for use against Kahtani, including the use of forced nudity, stress positions and the removal of religious items. In public statements, however, Rumsfeld has maintained that none of the policies at Guantánamo led to "inhumane" treatment of detainees. Jeffrey Gordon, a Pentagon spokesman, told Salon Thursday that Kahtani was an al-Qaida terrorist who provided a "treasure trove" of still-classified information during his interrogation. "Al-Kahtani's interrogation was guided by a very detailed plan, conducted by trained professionals in a controlled environment, and with active supervision and oversight," Gordon said in an e-mail statement. "Nothing was done randomly."

Miller -- who has invoked his right against self-incrimination in courts-martial of Abu Ghraib soldiers -- said that he did not know all the details of Kahtani's interrogation. But Schmidt told the inspector general that he found that claim "hard to believe" in light of Miller's knowledge of Rumsfeld's continuing interest in Kahtani. "The secretary of defense is personally involved in the interrogation of one person, and the entire General Counsel system of all the departments of the military," Schmidt said. "There is just not a too-busy alibi there for that."

The harsh interrogation of Kahtani came to an abrupt end in mid-January 2003. Gen. James T. Hill, Craddock's predecessor as the head of Southern Command, recalled in his interview with the inspector general that he received a call from Rumsfeld on a January weekend asking about the progress of Kahtani's interrogation. "Someone had come to him and suggested that it needed to be looked at," Hill said of Rumsfeld. "He said, 'What do you think?' And I said, 'Why don't [you] let me call General Miller.'"

According to Hill's account of that call, Miller advised that the harsh interrogation of Kahtani should continue, using the techniques Rumsfeld had previously approved. "We think we're right on the verge of making a breakthrough," Hill remembered Miller saying. Hill said he called Rumsfeld back with the news. "The secretary said, 'Fine,'" Hill remembered.

Nonetheless, several days later Rumsfeld revoked the harsher interrogation methods, apparently responding to military lawyers who had raised concerns that they may constitute cruel and unusual punishment or torture.

"My attitude on that was, 'Great!'" said Hill. The general recalled thinking about Rumsfeld and the decision to halt the harsh interrogation, "All I'm trying to do is what you want us to do in the first place and doing it the right way."

The harsher methods were not approved again.

-- By Michael Scherer and Mark Benjamin

Monday, April 03, 2006

Wasted Money & Broken Promises

"U.S. Plan to Build Iraq Clinics Falters

Contractor Will Try to Finish 20 of 142 Sites

By Ellen Knickmeyer

Washington Post Foreign Service

Monday, April 3, 2006; A01

BAGHDAD -- A reconstruction contract for the building of 142 primary health centers across Iraq is running out of money, after two years and roughly $200 million, with no more than 20 clinics now expected to be completed, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers says.

The contract, awarded to U.S. construction giant Parsons Inc. in the flush, early days of reconstruction in Iraq, was expected to lay the foundation of a modern health care system for the country, putting quality medical care within reach of all Iraqis.

Parsons, according to the Corps, will walk away from more than 120 clinics that on average are two-thirds finished. Auditors say the project serves as a warning for other U.S. reconstruction efforts due to be completed this year.

Coming with little public warning, the 86 percent shortfall of completions dismayed the World Health Organization's representative for Iraq. "That's not good. That's shocking," Naeema al-Gasseer said by telephone from Cairo. "We're not sending the right message here. That's affecting people's expectations and people's trust, I must say."

By the end of 2006, the $18.4 billion that Washington has allocated for Iraq's reconstruction runs out. All remaining projects in the U.S. reconstruction program, including electricity, water, sewer, health care and the justice system, are due for completion. As a result, the next nine months are crunchtime for the easy-term contracts that were awarded to American contractors early on, before surging violence drove up security costs and idled workers.

Stuart Bowen, the top U.S. auditor for reconstruction, warned in a telephone interview from Washington that other reconstruction efforts may fall short like that of Parsons. "I've been consumed for a year with the fear we would run out of money to finish projects," said Bowen, the inspector general for reconstruction in Iraq.

The reconstruction campaign in Iraq is the largest such American undertaking since World War II. The rebuilding efforts have remained a point of pride for American troops and leaders as they struggle with an insurgency and now Shiite Muslim militias and escalating sectarian conflict.

The Corps of Engineers says the campaign so far has renovated or built 3,000 schools, upgraded 13 hospitals and created hundreds of border forts and police stations. Major projects this summer, the Corps says, should noticeably improve electricity and other basic services, which have fallen below prewar levels despite the billions of dollars that the United States already has expended toward reconstruction here.

Violence for which the United States failed to plan has consumed up to half the $18.4 billion through higher costs to guard project sites and workers and through direct shifts of billions of dollars to build Iraq's police and military.

In January, Bowen's office calculated the American reconstruction effort would be able to finish only 300 of 425 promised electricity projects and 49 of 136 water and sanitation projects.

U.S. authorities say they made a special effort to preserve the more than $700 million of work for Iraq's health care system, which had fallen into decay after two decades of war and international sanctions.

Doctors in Baghdad's hospitals still cite dirty water as one of the major killers of infants. The city's hospitals place medically troubled newborns two to an incubator, when incubators work at all.

Early in the occupation, U.S. officials mapped out the construction of 300 primary-care clinics, said Gasseer, the WHO official. In addition to spreading basic health care beyond the major cities into small towns, the clinics were meant to provide training for Iraq's medical professionals. "Overall, they were considered vital," she said.

In April 2004, the project was awarded to Parsons Inc. of Pasadena, Calif., a leading construction firm in domestic and international markets. McCoy, the Corps of Engineers commander, said Parsons has been awarded about $1 billion in reconstruction projects in Iraq.

Like much U.S. government work in 2003 and 2004, the contract was awarded on terms known as "cost-plus," Parsons said, meaning that the company could bill the government for its actual cost, rather than a cost agreed to at the start, and add a profit margin. The deal was also classified as "design-build," in which the contractor oversees the project from design to completion.

These terms, among the most generous possible for contractors, were meant to encourage companies to undertake projects in a dangerous environment and complete them quickly.

McCoy said Parsons subcontracted the clinics to four main Iraqi companies, which often hired local firms to do the actual construction, creating several tiers of overhead costs.

Starting in 2004, the need for security sent costs soaring. Insurgent attacks forced companies to organize mini-militias to guard employees and sites; work often was idled when sites were judged to be too dangerous. Western contractors often were reduced to monitoring work sites by photographs, Parsons officials said.

"Security degenerated from the beginning. The expectations on the part of Parsons and the U.S. government was we would have a very benign construction environment, like building a clinic in Falls Church," said Earnest Robbins, senior vice president for the international division of Parsons in Fairfax, Va. Difficulty choosing sites for the clinics also delayed work, Robbins said.

Faced with a growing insurgency, U.S. authorities in 2004 took funding away from many projects to put it into building up Iraqi security forces.

"During that period, very little actual project work, dirt-turning, was being done," Bowen said. At the same time, "we were paying large overhead for contractors to remain in-country." Overhead has consumed 40 percent to 50 percent of the clinic project's budget, McCoy said.

In 2005, plans were scaled back to build 142 primary clinics by December of that year, an extended deadline. By December, however, only four had been completed, reconstruction officials said. Two more were finished weeks later. With the money almost all gone, the Corps of Engineers and Parsons reached what both sides described as a negotiated settlement under which Parsons would try to finish 14 more clinics by early April and then leave the project.

The agreement stipulated that the contract was terminated by consensus, not for cause, the Corps and Parsons said.

Both said the Corps had wanted to cancel the contract outright, and McCoy rejected the reasons that Parsons put forward for the slow progress.

"In the time they completed 45 projects, I completed 500 projects," he said. Parsons has a number of other contracts in Baghdad, from oil-facility upgrades to border forts to prisons. "The fact is it is hard, but there are companies over here that are doing it."

Sunday, April 02, 2006

Follow up -What ever happened to the American Taliban?

| An exclusive look at Lindh's life behind bars

| ||||

|

| ||||

| BY ADAM LISBERG DAILY NEWS STAFF WRITER | ||||

But there's really no other 25-year-old like John Walker Lindh. He will be forever tagged as the American Taliban, a California kid who converted to Islam and left home to find himself - and joined the radical Taliban to fight in Afghanistan. Now Lindh is serving a 20-year prison sentence, and is under a court-imposed silence. But Lindh's family and supporters say he deserves a break, and America needs to take another look at what he really did. |

"His story is indeed a story that needs to come out, and needs to be shared with the world," said Shakeel Syed, who served as a religious adviser to Lindh in prison.

"His story is indeed a story that needs to come out, and needs to be shared with the world," said Shakeel Syed, who served as a religious adviser to Lindh in prison.

In his first-ever account of Lindh's life in a medium-security federal prison in Victorville, Calif., Syed said Lindh is a model inmate who lives as normal a life as possible behind bars - but also is a spiritual beacon to other Muslims there.

"Prison has helped him become a better Muslim," Syed said. "He is a Malcolm X with a softer tone."

Lindh lives with a cellmate, works a prison job and is allowed to mingle with other inmates, Syed said - but he is prohibited from talking about his experiences in Afghanistan, can't see visitors who aren't relatives or lawyers, and isn't allowed to speak Arabic.

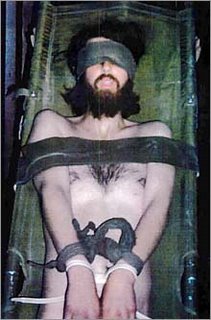

Contained ... this above shot of John Walker Lindh shows him bound naked in a container at Camp Rhino, near Kandahar, following his capture in December, say his defence lawyers, who released the photograph

While Lindh was taunted with cries of "Traitor!" when he first came to Victorville, and was once attacked by another inmate, he now faces no threats to his safety and even has gained a measure of respect, Syed said.

"He is an extremely well-liked, well-respected, model inmate in the system by the authorities as well as by the inmates," said Syed, now executive director of the Islamic Shura Council of Southern California. "Some of the inmates have come to sympathize with him because of his special restrictions."

Federal prison officials would not comment on Lindh or release information about him, citing privacy rules.

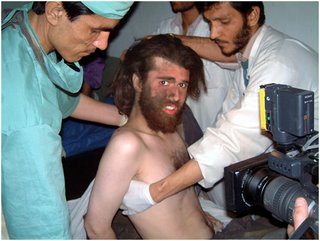

He burst into the public eye in November 2001, when CIA commandos working with the Northern Alliance, an Afghan group opposed to Taliban rule, found him among wounded and bedraggled Taliban fighters, who soon killed CIA operative Johnny (Mike) Spann.

The image of Lindh, filthy and exhausted, was beamed around the world - shocking the country with his unbelievable journey and stunning his parents, who hadn't heard from him in months.

Lindh had converted to Islam as a teen and traveled to Yemen to study the Koran and Arabic. When his visa expired he went to Pakistan, then sneaked across the border to Afghanistan - where he trained in an Al Qaeda-funded camp and twice met Osama Bin Laden.

Lindh's father, Frank Lindh, said his son was well-meaning but misguided, never taking up arms against America or joining Al Qaeda in its destructive quest.

"In simple terms, this is the story of a decent and honorable young man who became involved in a spiritual quest and became the focus of the grief and anger of an entire nation over an event in which he had no part," Frank Lindh told a San Francisco audience earlier this year.

But in the angry months after Sept. 11, Lindh was held up as a candidate for the death penalty.

Barely 10 months after he was seized on the battlefield, Lindh accepted a plea deal admitting he aided the Taliban - not plotting terror attacks or battling the U.S. He agreed to a 20-year prison term with no opportunity to appeal or challenge the government's restrictions while he's in prison.

Lindh's last public statement came when he was sentenced, where he tried to explain how he ended up in Afghanistan.

"I did not go to fight against America, and I never did," Lindh said. "I understand why so many Americans were angry when I was first discovered in Afghanistan. I realize that many still are, but I hope that with time and understanding, those feelings will change."

His parents have said little since then, but his lawyers are hoping a change in public mood could help him. With few legal options available, they've petitioned President Bush in a long-shot bid to shorten Lindh's sentence.

"I think we all have to realize that the odds are against it," Frank Lindh said in his San Francisco speech. "It is difficult to envision a situation where all those hotheads in Washington can turn around and recognize the kid got a raw deal and should be released."

Legal observers said the sentence was the byproduct of the national mood at the time, and note that many subsequent terror prosecutions in the U.S. have led to much shorter prison terms.

"He became an almost cathartic criminal case for the public," said George Washington University law Prof. Jonathan Turley. "Just as the public emotion was at a fever pitch, John Walker Lindh walked right out of central casting as a vicious traitor who betrayed his country. Upon further examination, he appears to be a confused kid playing a low-level role."

Originally published on April 2, 2006

KEY Words: American Taliban, John Walker Lindh, Books about John Walker Lindh, Google images of John Walker Lindh

Investigating the transformation of John Walker Lindh from a typical American teenager into the most infamous turncoat of our day, Kukis, a former UPI White House correspondent, traces the influences that played a part in Lindh's metamorphosis, from his California childhood to his capture in Mazar-i-Sharif. While unable to interview the young man himself (due, according to the publisher, to Attorney General Ashcroft's gag order) or his parents, the author draws from conversations he had with those who knew Lindh and witnessed his experiences-friends, teachers, lawyers, fellow students, family members and Taliban soldiers-all the way from San Francisco to Afghanistan, Pakistan and Yemen. Despite all the hype surrounding Lindh, Kukis "vowed to keep an open mind" in the research and writing of his biography, and expresses his hope that "understanding Lindh...will help us, as Americans at war, to reflect on ourselves as well as the enemies we face." B&w photos, maps. Copyright 2003 Reed Business Information, Inc.

Mahoney claims that his new book puts not only John Walker Lindh on trial but the entire U.S. government, for what he calls its treasonous double dealings with states that aid terrorists. Part biography of Lindh, part courtroom transcript, part military field report and in large part conjecture, the book, while often muddled and disconnected, raises important questions about the precarious nature of the U.S.'s alliances with Saudi Arabia and Pakistan. The author claims, as have others, that the U.S. enabled the rise of the Taliban by arming the mujahideen fighting the Soviets in Afghanistan in the 1980s. Most readers will find, though, that the charge that this constitutes treason ignores the complexity of the geopolitical landscape. Mahoney's second claim is that, because of its insatiable thirst for oil and profit, the U.S. habitually turns a blind eye to Saudi Arabia's and Pakistan's support of terrorism. The author's main charge, however, is that the Justice Department abruptly stopped Lindh's trial for fear of what might be revealed. This charge ignores what the judge noted: the evidence of Lindh's conspiracy to kill Americans was far from compelling, though Mahoney weakly argues the opposite. While providing much fodder for conspiracy theorists, Mahoney (Sons and Brothers: The Days of Jack and Bobby Kennedy) falls short of making his sweeping indictments stick.

Copyright © Reed Business Information, a division of Reed Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.